Introduction

Understanding the documentary modes allow us to see how documentaries shape their stories to engage audiences. These modes define narrative constructs throughout the film to connect people to real-life stories in ways that educate, inspire, and sometimes amaze viewers.

What makes documentary filmmaking truly amazing is how many different ways it can be approached. Think of the documentary modes as a giant creative toolbox that filmmakers can dig in to craft something special.

What’s even cooler is how flexible the art form can be. Filmmakers can mix and match different storytelling styles and techniques to create something that feels entirely fresh. This freedom to experiment and innovate is what makes the genre so exciting and, honestly, a little addictive to watch.

In 1991, American film critic and theorist Bill Nichols developed documentary modes to help us better understand this genre. The modes he identified, expository, reflexive, observational, performative, participatory, and poetic, serve as a guidebook to the various styles and approaches filmmakers use to tell their stories.

Like we’ll soon explore, each mode has its own personality and strengths, and together they showcase just how diverse and dynamic the world of documentary filmmaking can be.

What Are Documentary Modes?

A documentary mode is not a strict category. Think of it as more of a framework that helps us understand the different approaches and styles filmmakers use to construct arguments and represent reality.

Here’s the kicker: most documentaries don’t stick to just one mode. Filmmakers love to mix and match by borrowing elements from different modes to create something that fits their vision. For example, a film might use poetic visuals to set the mood but still rely on expository narration to drive home a key point.

This blending of styles is part of what makes documentary filmmaking so dynamic and exciting to watch.

So, why should you care about these modes?

Well, understanding them can totally change the way you approach your next documentary film project and even how you watch and analyze them.

When you know the choices filmmakers are making like why they’re using certain visuals, why the narrator’s tone is the way it is, etc.) you start to see the artistry and intention behind the work and can potentially allow it to inspire you in your next endeavor.

It’s not just about the story being told, but how it’s being told, and that’s where the real magic happens.

The 6 Documentary Modes

Here are the six main types of documentary genres:

- Expository Documentary

- Participatory Documentary

- Observational Documentary

- Reflexive Documentary

- Performative Documentary

- Poetic Documentary

Expository Documentary

Expository documentaries adopt a direct approach, presenting facts, arguments, and evidence to illuminate complex topics and guide the audience towards a deeper understanding.. These are the films that aim to educate or persuade you with crystal-clear arguments guiding you step-by-step through a topic with precision and authority.

This mode prioritizes intellectual engagement over emotional appeal or personal narrative, often employing a clear thesis or argument supported by meticulous research and expert opinions.. These arguments are persuasive because they often pack a punch when it comes to making their case.

“Voice of God” Narration

A hallmark of expository documentaries is the use of what’s called “voice of God” narration.

No, it’s not some booming voice from the heavens. It’s a narrator who speaks with authority by providing context, interpretation, and analysis. The voice ties everything together and gives the film a sense of structure and focus.

This narration isn’t casual or conversational. It’s polished, direct, and often scripted to perfection. It’s the voice that makes you go, “Okay, they definitely did their homework on this.”

Whether they’re dissecting complex science or unraveling a historical mystery, this narration is the backbone of the expository mode, and it’s what makes sure viewers walk away with a solid understanding of the topic.

Visuals That Do the Heavy Lifting

The narration doesn’t work alone. It’s also backed up by carefully selected visuals that reinforce the message. Archival footage is often used for this e (whether it’s old news reels, historical photos, or film clips from the time being explored).

There’s also b-roll, which are shots of landscapes, people, or events that keep things visually engaging. Sometimes filmmakers even use reenactments to bring moments to life, and this gives the audience a glimpse of what it might have looked like.

Cinematographers in this mode have a specific job: capture visuals that tell a story and support the facts. They are focused onclarity, impact, and giving viewers a window into the subject. Every frame works to make the argument stronger and keep the audience engaged.

Classic Example: The Civil War

Ken Burns’ The Civil War (1990) is a textbook example of the expository mode done right. This nine-part series dives deep into one of America’s most defining conflicts, not just recounting the events but analyzing their causes and long-term effects.

Burns blends beautifully narrated storytelling with a treasure trove of historical photographs, diary excerpts from people who served in the war, and period music to bring the era to life.

The narration guides viewers through the human aspects of the American Civil War in a way that feels accessible and deeply moving. It’s like sitting down with a well-read historian who also happens to be a master storyteller.

Participatory Documentary

Participatory documentaries are defined by the interaction between the filmmaker and their subject. While traditional documentaries often adopt an observational approach, where the filmmaker maintains a distance from their subjects, the participatory mode has emerged as a dynamic and transformative alternative.

In this mode, it’s about the dynamic between the filmmaker and the people or issues they’re exploring. The camera becomes a tool for interaction, and the filmmaker is therefore often a central part of the narrative.

Filmmaker as a Key Player

In a participatory documentary, the filmmaker must either be seen or heard at some point in the movie, giving them a presence that is often as important as the primary subject.

This approach challenges the conventional power dynamics between filmmaker and subject, fostering a sense of shared ownership and agency. By blurring the lines between observer and observed, participatory filmmaking creates a space for dialogue, co-creation, and mutual understanding.

They might be asking questions, challenging their subjects, or even experiencing the events alongside them. This mode is all about the filmmaker’s presence, their perspective, and how their involvement shapes the story being told. It’s a classic example of subjective storytelling, embracing the idea that no story is truly neutral.

This type of documentary often blurs the lines between filmmaker and participant, which makes it feel more like a conversation than a lecture. The audience gets to see not just the subject’s truth, but also how the filmmaker’s personal experiences and biases come into play.

Capturing the Interaction

Cinematographers in participatory documentaries have to focus on more than just the subject. They also need to capture the interaction between the filmmaker and their subjects. This can mean filming heated discussions (like where they capture moments of vulnerability) or documenting the filmmaker’s reactions in real-time.

The goal is to show the push and pull of the relationship, the emotional stakes, and the raw dynamics of these exchanges.

This style often feels intimate, as the audience gets a front-row seat to the conversations and confrontations that drive the narrative.

Standout Example: Bowling for Columbine

Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine (2002) is a prime example of the participatory mode. In this documentary, Moore dives headfirst into the issue of gun violence in America and he directly engages with his subjects, which include everyone from everyday citizens to corporate executives. His interactions often blend humor with hard-hitting questions, which creates a mix of observational and participatory storytelling that feels deeply personal and makes you think.

Observational Documentary

Observational documentaries are the ultimate “no filter” experience. Inspired by cinéma vérité (French for “truthful cinema”), this mode is all about stepping back and letting reality speak for itself.

This mode avoids narration, interviews, and flashy edits. It only portrays raw and unfiltered moments captured as they unfold. It’s as if the camera isn’t even there.

Fly-on-the-Wall Filmmaking

Often called “fly-on-the-wall” filmmaking, the observational mode is all about authenticity. The goal is to show people, places, and events exactly as they are, without commentary or manipulation.

This approach feels immersive, by putting the audience right in the middle of the action as a silent witness. It’s like being a guest in someone else’s world, where you get to watch things happen in real-time.

By minimizing filmmaker intervention, observational mode captures the raw and unfiltered reality of the subjects’ lives. The filmmaker allows the footage speak for itself, leaving room for the audience to interpret the story on their own.

Staying Invisible

Cinematographers working in the observational mode have one job: blend into the background. The camera isn’t there to perform or direct. It’s there to watch. This means no staged shots, no retakes, and no intrusive equipment.

The goal is to capture real and candid moments, so subjects can act naturally without feeling like they’re being put on the spot.

The result is footage that feels intimate and organic. The filmmaker is trying to keep it as close to “real life” as filmmaking can get.

Examples: Titicut Follies and The Salesman

One of the best-known examples of observational documentaries is Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies (1967).

This groundbreaking film takes an unflinching look at the treatment of inmates in a Massachusetts mental institution. With no narration or commentary, the camera simply follows the daily lives of the patients and staff, and in the process it exposes the harsh realities of the institution.

Another standout is Albert and David Maysles’ The Salesman (1969). This film dives into the lives of door-to-door Bible salesmen, and it captures their struggles, triumphs, and moments of vulnerability.

The Maysles brothers don’t interfere or guide the narrative. They let the camera roll as the salesmen hustle and interact with customers.

Reflexive Documentary

Reflexive films pull back the curtain to examine the relationship between the filmmaker, the audience, and the filmmaking process itself.In the process of doing so they often blur the line between reality and storytelling.

Breaking the Fourth Wall

Unlike other modes that try to immerse you in a seamless narrative, reflexive documentaries want you to know that what you’re watching is a construct.

They’re self-aware and make sure you are too. This can mean showing behind-the-scenes moments, addressing the audience directly, or revealing how decisions were made in the editing room.

It’s a mode that says, “This isn’t objective truth. It’s a version of reality we’re shaping.”

By highlighting the mechanics of filmmaking, reflexive documentaries make you question what you’re seeing and how it’s being presented. They’re like a mirror held up to the filmmaking process, asking you to think critically about the medium itself.

Filming the Process

Cinematographers in reflexive documentaries are focused on documenting the act of filmmaking. This could include capturing moments like interviews being set up, cameras rolling during off-the-cuff discussions, or even showing the editing process.

These behind-the-scenes glimpses create a meta-layer to the film, where the audience gets to see not just the story but how it’s crafted.

This approach creates a unique viewing experience where the audience becomes hyper-aware of the filmmaker’s choices. It’s less about presenting a polished product and more about pulling apart the seams to show how it all comes together.

The Ultimate Example: Man With a Movie Camera

Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (1929) is the gold standard of reflexive documentaries.

This silent film offers a day-in-the-life portrayal of urban Soviet life but does so while reflecting on the art of filmmaking itself. It shows the camera capturing life, editing techniques in action, and even reactions to the footage.

The film is actor-less, yet it feels alive with creativity. By turning the lens inward, Vertov not only documented daily life but also explored what it means to document at all. It was a groundbreaking work that essentially paved the way for reflexive documentaries as we know them today.

Performative Documentary

Performative documentaries are all about putting the filmmaker right in the middle of the story.

These films ask, “What does my personal experience have to do with the bigger picture?”

In this mode, the filmmaker takes you on a journey through their own life to highlight a larger truth about society, culture, or history. But unlike the participatory mode where the filmmaker interacts with the subjects of the narrative, in the performative mode the filmmaker actively participates directly in the narrative.

The Filmmaker’s Personal Journey

In performative documentaries, the filmmaker is the central part of the story. The whole point is to explore bigger societal or cultural issues through their personal experience.

You might see the filmmaker struggling, reflecting, or even changing as they get deeper into the topic. It’s much more personal than a participatory documentary. This mode focuses on the human side of things, and makes you feel like you’re experiencing it all firsthand through the perspective of the filmmaker.

Instead of just telling you about an issue, the filmmaker dives in headfirst and shows you firsthand through their own experience.

Cinematography: Capturing the Journey

Cinematographers in performative documentaries have the tricky job of not just capturing the subject matter but also the emotional and personal side of the filmmaker’s journey.

Their goal is to make you feel like you’re walking in the filmmaker’s shoes seeing things through their eyes and experiencing the emotional highs and lows along with them.

This can include personal moments that feel raw and unfiltered, whether it’s a breakdown or an “aha” moment.

The Perfect Example: Supersize Me

Take Morgan Spurlock’s Supersize Me (2004).

Instead of just talking about how unhealthy fast food is, he becomes the experiment itself.

He eats nothing but McDonald’s every day for a whole month, and you watch as it takes a serious toll on his body.

In the process, his personal health struggles become a bigger commentary on the fast food industry, corporate culture, and public health in general.

Poetic Documentary

Poetic documentaries transcend the conventional reliance on linear narratives and factual exposition, instead prioritizing mood, tone, and the evocative power of imagery.

These films don’t aim to explain. They aim to make you feel.

Breaking Free from Traditional Storytelling

Unlike other modes, poetic documentaries ditch linear narratives and traditional storytelling structures. There’s no beginning, middle, or end in the conventional sense.

Instead, these films weave together a series of visuals and moments that evoke emotions or reveal deeper truths about the subject. Watching a poetic documentary feels more like experiencing a visual poem or a dream rather than a lesson.

Cinematography: Pure Visual Poetry

Cinematographers in poetic documentaries are like painters with a camera. Every frame is carefully crafted to be striking and meaningful, often with little or no dialogue to guide the viewer. Instead of focusing on facts or events, the imagery takes center stage, relying on its beauty and symbolism to communicate.

For example, you might see slow-motion shots of water rippling, shadows dancing on a wall, or a close-up of a single hand moving through grass. Each shot feels like its own work of art, working together to create an emotional or thematic resonance. The visuals speak for themselves, often accompanied by carefully chosen music or natural sounds to amplify the mood.

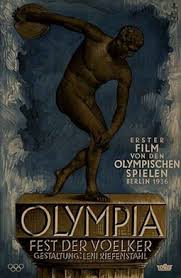

The Classic Example: Olympia

Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938) is a standout example of the poetic mode.

This documentary about the 1936 Berlin Olympics utilized powerful imagery and artistic composition to capture athletes in ways that elevate their actions to something almost mythical.

From slow-motion shots of pole vaulters soaring through the air to dramatic angles of runners in motion, every frame felt deliberate and awe-inspiring in its own right. This film was not meant to be a record of the Olympics. Instead, it was an exploration of the human form and spirit that just so happened to be filmed at the 1936 Olympics, and it was told through visuals that left a lasting impression.

Conclusion

If there’s one thing that you take away from this article, it should be that documentaries are as diverse as the stories they tell.

They can capture raw and unfiltered moments, dive into personal experiences, or create emotional and visually stunning art. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach.

If you’re considering your next documentary project, understanding these modes are a great starting point if you’re not yet quite sure about what you think your documentary will look like.

The best part? You don’t have to stick to just one. Mixing and matching between modes can be half the fun, and is often where the magic happens.

If you’re still feeling stuck or a little unsure, don’t hesitate to reach out. Sometimes it just takes a fresh perspective or a little advice to get things moving!